Wednesday, September 19, 2012

A River Story: The Stirring and Piteous Case of an Old Fashion Homestead Razing

It’s a late August morning when I arrive and pull my truck to the side of the road. In the years since I’ve last been here last, the road’s been paved wider and there’s barely enough room for me to park the truck on the gravel shoulder. There’s far more traffic too, even at this early hour and even for this quiet road. One car races by, narrowly missing me. I reserve little doubt that the motorist clearly saw me. He attempted instead to make a point of his nausea with me being parked so close to, what he contemptuously believes to be his own personal thoroughfare. Replying with an illustration of my own subtle distain, I hoist a single fingered salute in his direction.

The air is cool, you might even say brisk, but this August has been hotter than any I can remember. In a few hours I’m sure it won’t disappoint. A band of murky orange clouds smolder on the eastern horizon where the sun promises to rise. To watch the sky lighten in the still air of the morning is a privilege that I indulge myself in. I concluded long ago that sunsets are for hapless poets, teenage lovers, and people who have apparitions of enjoying nature but only within the confines of human convenience. But sunrises on the other hand must be earned. Watching the sun rise out over the world takes an act of purposeful discipline.

I begin attending to the job of removing the canoe from the roof of my truck. The night before, in what can only be described as a spectacle of sweat, swirling mosquitoes and uncontrolled convulsions of four-letter words, I affixed the ancient behemoth to the Ford and looking at it now, adhered so neatly, I hardly dare remove it. The 1952 Grumman is a relic of whose origins remain a mystery. It was a fixture alongside our family’s barn in south-eastern Wisconsin for as long as I can remember. It’s dented, scratched and has three holes in the bottom that suspiciously look as if they were put there by a 45 caliber pistol. My dad, seizing an opportunity at masculine ingenuity, had run half-inch bolts through the holes and from time to time a healthy dose of rubber silicone glue was needed to ensure its seaworthiness.

Rendering a slapdash verdict, I raise my knife to the ropes that held the canoe steadfast and cut them. Pulling the beast from the roof it’s suddenly like a whale out of the water as it tumbles to the ground. I jumped back anticipating it smashing into me like a spooked horse. After a few moments of convulsing wildly it comes to a rest. Much older than the 10 year old boy of my past, who needed to con unsuspecting friends into helping me to drag it, I now easily lift it from the bow and pull it along the gravel and to the banks of the river. The aluminum across the gravel is like the screeching of a Martini-pickled mother-in-law. But once at the bank, and after sliding the oversized tin can into the water, it becomes a different beast all together. The canoe is light and nimble as the unseen fingers of current tug gently at the hull and with a slight hop, we’re off.

The river is an old friend and looking back, I must admit rather grudgingly, one of my better ones. Growing up a farm kid, the river running through our property was as much a part of my childhood as my mom and dad, the sandbox, the old green barn to the north of our house or the tire swing tied to that massive red oak. It feels like home, but I prepare myself. This is to be a trip paid in homage, it is a good bye of sorts, a journey along a path that will take me thorugh flashbacks of my childhood, innocent and carefree but end in a sudden, undeniable modern realization of what lies ahead for this river.

The sun has just begun to peek above the horizon as I round my first bend. Streams, creeks, rivers, whatever you call them, they are engrained into our conscience, they are history before us, a story of time written across the landscape. They carried Native Americans along routes to sacred hunting grounds and the earliest explorers paddled them into wild and untamed new worlds. Their power is unimaginable. They can flood their surroundings in seconds, destroying all that lie in their path, and yet in the same breath gently bring water from far off sources to the forests and fields downstream, spreading life. This river knew me as a pink shouldered boy too young yet to notice girls, when I knew nothing of IRAs, and before I knew houses could be upside down. The world since then has grown and yet time seems to have frozen this place into a museum. Progress has not yet made it to the banks of this river. Gliding silently along, there is only the cadence of my paddle and the drops of water that fall from it. Peering into the heavily canopied forest, there is a light fog still clinging stubbornly to the forest floor. The sunlight has just now broken through the leaves, spilling scattered puddles of light across a mossy green carpet. Huge cottonwoods, weeping willows and silver birch line the shores; years of flood and frost have mangled their low hanging branches into the shapes of dilapidated play ground equipment, long deserted. These magnificent trees seem almost watchful over me, their roots imprisoning them to an eternal guardianship over this place. Like giant soldiers from a JRR Tolkien novel, they peer down as I float by.

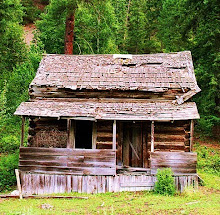

My nostrils are suddenly filled with the rich and heavy scent of rain in the distance. The muggy August morning is about to fracture. A gentle rolling breeze has kept the bugs at bay and the sun is now a phantom behind the clouds. A crack of thunder in the distance dazes me into a foggy memory of youth. It was near this spot that I once came as close to death as a young 15 year old might. In the summer before my freshman year, I had stuffed a pack with modest provisions and canoed 6 or 7 miles downstream from my house. The river was low that summer. We had been plagued with drought for months and where water had traditionally been shallow, numerous sandbars had now formed. It was one of these sandbars I thought would be a perfect place to build camp. Feeling rather smug, I built a fire and cooked rations of Spam, stolen from my mother’s cupboard and watched the sun sink in the sky without a care in the world. Sometime around 2 am that night, I awoke to the clap of thunder and the gentle pitter-patter of rain on my tent. With-in seconds the pitter-patter had turned to a hammering down pour. Reaching for my lantern, I looking down and noticed water several inches deep. During a normal summer the sandbar would be under seven or eight feet of water. A massive lump formed in my throat. Rushing from my tent, I searched for the canoe, but it was gone. I had failed to tie it to anything the night before, feeling no need to do so. In a panic, I tried gathering up my camping gear, a foot of water was now swirling at my ankles. As I un-staked my tent the true power of a mere twelve inches of water made an ever-lasting impression on my psyche as the water pulled the tent effortlessly from my clinched hands. Somehow I managed to grab my life jacket seconds before the tent vanished into the blackness of the raging storm. Just as the current knocked me from my feet, I was able to wrestle it on and a watery abyss suddenly enveloped me. To this day, I have never experienced anything like it. Suddenly, over the roar of the rain and thunder, to my ears came what I can only describe as a low, thundering growl, rumbling through the blackness. Gasping for air and being tossed like a rag doll, my head pulled under, then back above, I was suddenly hit square in the face by what felt like a brick wall. In an instant, I found myself completely submerged and unable to tell neither which way I was facing, nor which way was up or down. I surfaced what felt like several minutes later, only to find myself in the center of an electrical storm beggaring description. Lightning flashed everywhere and my surroundings looked as though they were being illuminated by a strobe light. A seemily foreign world enveloped me, catching glimpses of my surroundings only in erratic flashes. It completely disoriented me. The water slammed me from one side of the shore to the other. Low hanging branches reached for me like the cold boney fingers of the grim reaper. And then everything went black. I’m not sure how long I was out, but I woke suddenly, on my back and staring up at a full moon and wispy gray clouds. A dull pain throbbed in the back of my head and I could still see faint flashes of lightning in the distance as the passing storm raged on to the east of me. Finding myself floating in a backwater eddy, I peered through the moonlit darkness at an unfamiliar looking river bloated with flood. Paddling myself into the main current, I let it take me. Barefoot and having little more on than some cut off jeans, I was 10 miles from home and floating now in the wrong direction all together. I was without my canoe and without any supplies. Drifting along for what seemed to be an hour, I caught a glimpse of something silver and foreign in the inky blackness ahead. Tangled in the branches of an old willow tree was the canoe. Swimming to it, I somehow monkeyed myself into the hull. I waited the night out cold, alone and with a new found respect for the river, water, and the wild. The next day to my relief I discovered I was only a short mile from where the river went under the bridge at old Highway 67. Once there I flagged down a driver who took a chance on a skinny half naked kid alongside the road. Now all these years later I’m peering down into the same water, clear as gin, sad I suppose that this is the last I’ll ever see it so lucid, so pristine, and so untouched. Not more than a half mile to the north lay the unmistakable manifestation of Progress. A vast cesspool of new construction, land, that only weeks ago looked very much as it had for over a hundred years, now stands absolutely devoured. The area, once a family farm, tilled by countless generations, is a wasteland where the preemptive stages of what they call growth now stretch out over a thousand acres. It is a landscape void of any character or reason. Farming has always been hard work, and it never paid well. Even as the government seemed to come to its senses during the 1980s, passing legislation that helped families keep their farms, Big-Farm-a, as I call it, squeezed the chance at any real profit from the husband and wife dairy farmers. Tyrants have long realized that land is a scared birth-rite, and to take it, by means of taxation, bribery, eminent domain or rapacious persuasion is a psychological means of warfare, leading to eventual slavery by the state. Regardless of the terms of this sale, the signatures on the contract weren’t yet dry when the army of bulldozers, excavators, back-hoes, and dump trucks laid siege to the land. The mayor with various cronies of political hierarchy were there to witness the groundbreaking, as were some lawyer types, developers, bankers and investors. Standing in the middle of the chaos that was to be, stood the empty farmhouse, the symbolic enemy, what it represented was in sharp contrast to everything the developers planned on building in its place. The razing of the old homestead was to be celebrated by the pale-faced hacks who watered at the mouth by the mere thought of its demise. A lone bulldozer set forth at accomplishing the task at hand. It came from the north and struck the house with full force. The lawyers and the banker-backed developers stood in perverted anticipation. But the structure did not immediately fall. The operator looked on in amazement. He readied the machine for another blow. The mayor peered on with distain, how this dilapidated little shack dare stand in the way of progress he thought. The bulldozer struck again with full force. The old farm house shuttered but stood on rebelliously. But in the end, it was only made of wood, and the bulldozer of iron, fueled by diesel, greed and the full momentum of progress behind it. When the house was gone the mayor and the stiffs in the suits stood triumphantly for pictures on the newly conquered ground. Construction trailers were brought in at once and placed at the site of the old homestead and a flag was raised in victory over the farm. And then began the rape and pillage. Earthmovers rolled in, by the dozens. There was a sick feeling of inhumanness that hung in the air; a sense of an almost robotic, unfeeling movement. Nothing with a soul could do what was being done there. The machines sheared the ground and peeled earth back, crops still in place, like skin scalped from the skull. Total destruction and extermination of any human spirit left in this place was the goal. With-in a few days the once teaming landscape was reduced to a barren wasteland. Dust blew across the real estate as if it were a desert. There was about as much life left there as was on the moon. So much as I once believed that a God would never allow such a faith befall this place, I also now come to the realization that it is lost. A family of Canada geese floats past my canoe, a proud hen with five goslings in tow. A nervous gander swims at a distance and gives me the evil eye. Martin Luther King, Jr. said once, “if I knew the end was to come tomorrow, I would still plant my apple tree.” The tiny family swims on and out of sight, unaware of the destruction that awaits them. Or perhaps they are all too aware and instead wish to heed the mind set of Dr. King and swim on. My take out spot is just ahead. I have stashed a bike somewhere there in the cattails as a means by which to get back to my truck some twelve miles or so upstream. I’ve been to this place many times before. Here the river narrows and the water flows faster than anywhere else. A chessboard of rocks sticks out from the surface and the water rushing around them is like a chorus. I used to love spending time here at the end of each trip simply sitting and listening to the water. So assuring was that sound, assuring that there existed something so much more complex than our own derisory existence. Assuring that something as random as rocks placed in the water by time could reverberate a sound so diverse in its simplicity. These waters have called to me my whole life. From the pre-pubescent boy who gathered river rocks, to the adolescent who tried to forget the hardships of high school here or the young man who sat in this very spot trying to gather the courage to tackle the life ahead of him, I have relied on this river for so much strength, and now there is nothing I can do to protect it. I pull the canoe from the water one last time, leaving it in the bulrushes a dozen or so feet from shore as a fitting final resting spot, here at the river where it belongs. As I walk to the road, I can hear the water behind me. It’s a sad voice that seems not to understand my parting. I don’t answer, I simply turn my back and walk away.

Monday, September 17, 2012

Evertte Ruess, Mystery of the American West

(Posted as it first appeared in The Prairie Times, Elbert County, Colorado, January 2010).............................................................In the autumn of 1934, a pair of sheepherders in the middle of the Utah wilderness were rather taken aback when a boy, no more than twenty years old, alone and riding a burro, happened into their camp out of nowhere. As twilight gave in to night, the threesome sat around an arid desert campfire. Their topic of conversation can only be speculated at, however, Everett Ruess, the burro riding boy, almost certainly did the majority of the talking. The sheep wranglers probably sat and listened, somewhat suspiciously, as Evertt told them of how he had been born in California and that at age 16 saddled a burro and traveled east and into the desert wilderness with little more than provisions of raisins and rice. And perhaps the pair grew even doubtful of this young man’s sanity as he explained how he had traded works with the famous American West artist, Maynard Dixon or how he had been the photography subject of the prized photojournalist Dorothea Lange. Regardless of what the shepherds thought of this boy’s stories, they decided they liked him, and as morning dawned out across the painted desert, Everett Ruess would break from camp, his new friends giving a gentle wave as he rode off.

He would never be seen again, vanishing forever into the serene Utah wilderness.

Sometime later a search party of Escalante cowboys would come across a makeshift camp, and two burros, but Everett Ruess now belonged to the ages.

And so began the legend.

Almost six decades before Chris McCandless would venture into the north expanses of Alaska on his own attempt “to kill the false spiritual being with-in”, Everett Ruess trekked into the vast American West, exploring the Canyon de Chelle, Grand Canyon, and what is now Yosemite and Sequioa National Parks.

And he did it alone.

His travels are well documented by photographs, journal entries and letters home to his parents, but rich with legend and myth. His motives were largely unknown, and his eerie disappearance only fuels the cult like following in certain American history circles.

So when in March of 2009 a small group of individuals from the University of Colorado had announced they had found the remains of the most famous missing person in the history of the American West, some had feelings of melancholy ripple through their hearts.

The discovery actually began in November 1934, when Aneth Nez, a Navajo indian had noticed a young white man roaming the area around Comb Ridge in the Utah wilderness. A week later Nez witnessed the same boy rundown, murdered and robbed by three Ute natives. Because of rising tensions between the Navajo and Ute at the time and for fear of government retribution because a white boy had been murdered at the hands of Native Americans, Nez said nothing. He instead waited until almost sundown, gathered the boy’s remains and buried them in a small crevasse on a near by ridge. That story would remain his secret until 1971, when he confessed the tale only to his daughter and a Navajo medicine man. His daughter, Daisy Johnson, facing her own mortality some 40 years later, confided in her brother Denny Bellson of their grandfather’s amazing confession. Bellson, who lived just minutes from the area where Aneth Nez had seen the boy murdered, was gripped with a passion to find the site where his father had said he buried the boy in the fall of 1934. Over the next several weeks, Bellson searched the Comb Ridge area looking for the grave. One day he came across an almost indiscernible crack in the sandstone. He peered through the narrow fracture and there at the bootom of the shallow crevasse, he found the scattered bones of a human skeleton.

In the year that was to follow, the FBI would investigate the scene and conclude it was that of a traditional Navajo burial. DNA would be taken and compared to relatives of Everett Ruess’s, and found to be inconclusive. It seemed the Everett Rues mystery was to remain just that, a mystery. Then in January 2009, a team of experts in Navajo archeology and a forensic anthropologist from the University of Colorado in Boulder returned to the site to give the remains the proper forensic examination they had deserved. By early 2009, they had reconstructed the skull and examined enough of the bones, comparing them to physical descriptions and excellent photographs of the living Ruess to come to the, in their opinion, positive conclusion that the remains found on the Comb Ridge were in fact those of Everett Ruess. “I’d take this to court. This IS Everett Ruess.”, said Dennis Van Gerven, the anthropologist in charge.

However, just when relatives were ready to take custody of the bones found in the desert crevasse, they decided on a second opinion, urged on by Utah state archeologist, Kevin Jones. The Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory conducted the new DNA tests and concluded that the DNA samples irrefutably proved the body in the Utah desert, found by Denny Bellson, were not that of long famed Evertt Ruess. Ruess’s family has accepted these results as final.

Van Gerven, from the Boulder, Colorado study, still argues his bone comparisons are evidence enough that the remains cannot be anyone else’s but Ruess.

So once again, it seems for now at least, the American West is united with one of its greatest unsolved mystery. Or maybe perhaps we like to still believe that in this world of satellites and thermal imagining, micro-processors and DNA spiral helixes, that there are some mysteries, some unsolved stories and romances of the wilds we’d rather just not have the answer to. Whatever the case, whenever we venture out, into a wild world we’ve never been, we still evoke the feeling in ourselves that people like Ervertt Ruess, Thoreau, and Muir understood. We stand beside them, and we hear the whispers as the wind ripples across the ridges and through the ancient pine laced canyons. Go out, explore, live, and never cease to wonder.

Ben Fulton, “Utah Scientists question Everett Ruess DNA Findings”, Salt Lake Tribune, 02 July 2009

David Roberts, “Finding Everett Ruess”, National Geographic Adventurer, 01 May 2009

Paul Foy, “Remains Found in Utah not poet Everett Ruess”, Associated Press, 21 October 2009

Wednesday, September 12, 2012

A Peculiar Odyssey of Survival, Revenge and Retribution; The Unbelievable Tale of Hugh Glass.

A New Year’s Eve squall blew hard outside Fort Henry, a dilapidated scattering of trapper’s cabins in what is now modern day Yellowstone Park. The year was 1823 when, at the door appeared a grizzled and near lifeless silhouette. The crowd inside, a fur trading expedition surely a bit inebriated from the celebratory sour mash, looked on with shock at the figure in the tavern’s vestibule. Surely it must be a ghost they thought, a ghost from their past. But the man at the door, his eyes slivered in hate was very much alive.

And the trip he had endured over the past 4 months is quite possibly the greatest feat of human endurance in history.

In August, 1833, Hugh Glass, all ready a well known trapper, replied to an advertisement placed in the Missouri Gazette by General William Ashley. General Ashley desired 100 brazen men to forge a new trapping route north through the uncharted wilderness of the Missouri River Valley. Glass’s wilderness resume’ was impressive. As a young man he had been attacked, held captive and then sentences to death by Pawnee Indians. The day of his scheduled execution, in a state of affairs, which to this day remains a mystery, Glass was not only able to convince the chief to spare his life, but later adopt him as an honorary Pawnee Indian. General Ashley was so impressed with Glass that he hired him almost at once.

Shortly after the expedition began, the General appointed a member of the group, a Mr. Andrew Henry to lead 13 men further up the river, through the Yellowstone Valley and to relieve traders at Fort Henry. Hugh Glass was among the men chosen to make the five month journey. It was hard, difficult country, a land of big valleys, gorges cut out of solid rock and to the east, the Great Plains that stretched to Mexico in the south and the Mississippi to the east. It was also dangerous land, filled with hostile and unreceptive Native Americans. The most intolerant of these tribes were the Arikara. The Arikara, originally a peacefully people from the Dakota Territory had, by 1830, almost vanished from slaughter and their populations run thin by small pox.

Ironically, it wasn’t Indians that Hugh Glass encountered on a warm August day, it was instead a grizzly bear he surprised not far from camp. Glass had rounded a bend on a deer trail and come upon a large female grizzly. Startled, the bear charged. The hunter was unable to raise his rifle in time, and the bear hit him with the full force of a freight train. Five inch claws slashed and massive jaws clamped down on his head and shoulder, viciously shaking the hunter about. Glass was a stubborn survivor and even against the 900 pound bear, he proved somewhat difficult to kill. Grabbing his knife, Glass swung back fiercely. His swings were accurate and deliberate, and when the other trappers arrived, having heard the roars of the bear, they found a appallingly wounded Hugh Glass, lying next to a lifeless bear.

In the attack, Glass had suffered a broken leg and arm. The skin on his upper back had been peeled back like an orange and his face, neck, and scalp were ripped and torn from numerous swings of the bear’s claws. The first responders initially thought Glass was dead. It was not until Andrew Henry, the expedition’s leader arrived that Glass let out a weak and obscure groan, shocking the gathered trappers. Gasping for air and bleeding profusely, Henry was certain the man would hardly live another hour. At the time of the attack, the group was breaking camp and intended to head out as soon as possible. They were in the heart of Arikara country and could hardly afford to wait any longer. Henry, a devote Christian, felt it necessary that Hugh Glass receive a proper burial. He asked for volunteers, and when no one stepped forward, he upped the ante. Henry included a hefty bonus to whoever would stay back with Glass, and bury him when he died. A young man near the back of the crowd, Jim Bridger, a boy of only 17 stepped forward. He was in desperate need of money and the promise of an extra bonus, equivalent to one month’s pay was irresistible. Another man, Thomas Fitzpatrick volunteered for the extra money. Henry’s volunteers would not likely wait long for Glass’s death and would follow the expedition’s trail north and then west and catch up in a few days. Almost at once, the rest of the trappers pulled up stakes and headed up the Missouri River and out of the dangerous Arikara Indian country.

The others were no sooner out of sight than Bridger and Fitzpatrick began digging Glass’s grave. Once dug, they rolled him into it, where he landed with a thump, and covered him with a large buffalo hide and waited. What the volunteers thought would be a quick death turned out to be nothing of the sort. The old honorary Pawnee Indian was a stubborn old warrior and refused to die. What Bridger and Fitzgerald though would take minutes, lagged into hours, and as night began to fall, the two white men became increasingly nervous of the looming danger of the Arikara. Throughout the night, Glass fell in and out of consciousness. His gurgled gasps for air likely drove the two volunteers nearly mad. Somewhere in the darkness of night, the two fell asleep. As they awoke in the morning, they fully intended to find Glass dead. But he was not. Fitzgerald argued to leave Glass where he lay, and make a run for it. It was only a matter of time before an Arikara hunting party would pass their way. Bridger strongly opposed leaving the near dead Glass, but the elder Fitzgerald’s perseverance finally triumphed and he and Bridger grabbed Glass’s prized Hawken rifle, his hunting knife, and other provisions, threw a few shovelfuls of sandy earth on top of him and hurried up stream to catch up to the expedition. Early the next morning the duo caught up with Henry and the others and reported that Hugh Glass has succumbed to his injuries and was now dead and buried.

That should have been the end of that.

However, in the hours after Bridger and Fitzgerald’s hasty retreat, Glass on some detached and dim level of consciousness, mustered enough strength, through either pure will power or pure resentment, to sit up in his own shallow grave. The world around him was burly, but he was fully aware that he had been betrayed. Perhaps the rage now brewing ever stronger helped to pull him from the grave. Once on flat ground, he set his own broken leg. Glass knew he was literally hundreds of miles from safety and was in the middle of hostile Arikara country. An expert on wilderness living and survival he knew safety lie only in Fort Kiowa, some 250 miles to the west. Unable to stand, Glass began to crawl. His wounds were infected so badly that the skin began to die. Somewhere along the route, fearing gangrene, he tipped a rotting log and under it found a slew of maggots, at which point he laid his injured back into the squirming pile until they hate ate away the dying and infected flesh.

Meanwhile, the original expedition had traveled up along the Missouri River and then later the Grand River. Glass knew that this would be far too dangerous an endeavor so he chose to crawl south, to the Cheyenne River.

And crawl he did.

For six weeks.

He had set his leg, but it was still too badly broken to support his weight. He ate berries and robbed ground-nesting birds of their eggs. He crawled to a recent buffalo kill and stayed three days at its side eating the meat. When he made it to the banks of the Cheyenne River, sometime in mid-September, his wounds had almost entirely healed. On the river’s bank he fashioned a crude raft and took the river into Fort Kiowa, another two week journey. He survived on frogs, raw minnows and river slime scooped by hand. Finally, upon arriving in Fort Kiowa in the cold days of early October, Glass rested only a few short days before hitching up with another trapping outfit headed in the direction of The Bighorn River. He planned, once at the Big Horn, of leaving the outfit to hunt down his old party and seek revenge on Bridger and Fitzgerald. The trapping outfit he was traveling with to The Bighorn River was being led by an experienced woodsman named Toussaint Charbonneau. Somewhere, miles into the trip, the party suffered hostile native attacks that left all but Charbonneau and Glass dead. Glass had once again narrowly escaped death. Afterwards, Glass parted ways with Charbonneau, who chose to continue traveling west with a tribe of Mandan Indians.

It would be a snowy December night before Glass finally arrived at Fort Henry at the mouth of the Yellowstone River. The past four months had taken him over 600 miles across the most dangerous land in the Western reaches of the United States. By this time, he was again nearly starving and pushed on by what can only be speculated as pure hate and revenge. As he opened the door to the tavern where the company of his former expedition now sat, merrily gulping holiday ale, celebration must have surely turned to disbelief. Shock filled the room and a nervous Bridger stepped back and into a far corner of the open room. Glass held no reservations as to why he had come and boldly announced he was there to kill Bridger and Fitzgerald. Pacing the room until he found Bridger, the old trapper lowered his rifle in line with the 17 year old boy. Bridger, who had every intention of staying with Glass, was so shocked and his guilt so apparent, that Glass, the hardened man who had crawled two months through a living hell, the man who hid from Indians, watched members of his own party murdered and ate rotting meat from the corpses of animals, forgave him almost immediately. But, the older Fitzgerald was another story. Glass asked the whereabouts of Fitzgerald and Andrew Henry had to inform Glass, that Fitzgerald had quit the expedition to join the Army. Upon hearing this news, Glass halfheartedly joined the trappers in the New Year’s celebration, but, as he drank the warm beer, his mind was on Fitzgerald.

In the days that followed, Glass acquired as much information as he could regarding the current location of Fitzgerald and tracked him to an army installation in Fort Atkinson, 30 miles north of modern day Omaha, Nebraska. It was the early summer months of 1824. Glass was stopped shortly before entering camp by the army Captain Bennett Riley. For months, word had spread of Glass’s search for the solider Fitzgerald and Captain Riley was not in any mood to have a man under his command murdered. Informing Glass that killing a soldier in the United States Army would result in his hanging, Glass reserved himself. He asked only that Fitzgerald return to him his prized Hawken rifle, to which Fitzgerald complied.

And then Glass disappeared.

An account of Glass being wounded by arrow one year later would surface in Naval medical records and it is known that he survived the attack, but nothing was to be written, or heard of Hugh Glass afterwards.

In a tale that could only have originated in the vast expanses of the American West, Glass embodied the grit, determination and sheer will power of the early American spirit. His intentions slightly skewed, he never the less survived a mountain man’s peril, and then appropriately and fittingly vanished into legend.

Bruce Bradley, Hugh Glass, 1999

John Myers, The Saga of Hugh Glass: Pirate, Pawnee and Mountain Man, 1976

Robert Mc Clung, Hugh Glass: Mountain Man, Left for Dead, 1993

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)