Wednesday, September 12, 2012

A Peculiar Odyssey of Survival, Revenge and Retribution; The Unbelievable Tale of Hugh Glass.

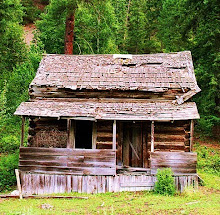

A New Year’s Eve squall blew hard outside Fort Henry, a dilapidated scattering of trapper’s cabins in what is now modern day Yellowstone Park. The year was 1823 when, at the door appeared a grizzled and near lifeless silhouette. The crowd inside, a fur trading expedition surely a bit inebriated from the celebratory sour mash, looked on with shock at the figure in the tavern’s vestibule. Surely it must be a ghost they thought, a ghost from their past. But the man at the door, his eyes slivered in hate was very much alive.

And the trip he had endured over the past 4 months is quite possibly the greatest feat of human endurance in history.

In August, 1833, Hugh Glass, all ready a well known trapper, replied to an advertisement placed in the Missouri Gazette by General William Ashley. General Ashley desired 100 brazen men to forge a new trapping route north through the uncharted wilderness of the Missouri River Valley. Glass’s wilderness resume’ was impressive. As a young man he had been attacked, held captive and then sentences to death by Pawnee Indians. The day of his scheduled execution, in a state of affairs, which to this day remains a mystery, Glass was not only able to convince the chief to spare his life, but later adopt him as an honorary Pawnee Indian. General Ashley was so impressed with Glass that he hired him almost at once.

Shortly after the expedition began, the General appointed a member of the group, a Mr. Andrew Henry to lead 13 men further up the river, through the Yellowstone Valley and to relieve traders at Fort Henry. Hugh Glass was among the men chosen to make the five month journey. It was hard, difficult country, a land of big valleys, gorges cut out of solid rock and to the east, the Great Plains that stretched to Mexico in the south and the Mississippi to the east. It was also dangerous land, filled with hostile and unreceptive Native Americans. The most intolerant of these tribes were the Arikara. The Arikara, originally a peacefully people from the Dakota Territory had, by 1830, almost vanished from slaughter and their populations run thin by small pox.

Ironically, it wasn’t Indians that Hugh Glass encountered on a warm August day, it was instead a grizzly bear he surprised not far from camp. Glass had rounded a bend on a deer trail and come upon a large female grizzly. Startled, the bear charged. The hunter was unable to raise his rifle in time, and the bear hit him with the full force of a freight train. Five inch claws slashed and massive jaws clamped down on his head and shoulder, viciously shaking the hunter about. Glass was a stubborn survivor and even against the 900 pound bear, he proved somewhat difficult to kill. Grabbing his knife, Glass swung back fiercely. His swings were accurate and deliberate, and when the other trappers arrived, having heard the roars of the bear, they found a appallingly wounded Hugh Glass, lying next to a lifeless bear.

In the attack, Glass had suffered a broken leg and arm. The skin on his upper back had been peeled back like an orange and his face, neck, and scalp were ripped and torn from numerous swings of the bear’s claws. The first responders initially thought Glass was dead. It was not until Andrew Henry, the expedition’s leader arrived that Glass let out a weak and obscure groan, shocking the gathered trappers. Gasping for air and bleeding profusely, Henry was certain the man would hardly live another hour. At the time of the attack, the group was breaking camp and intended to head out as soon as possible. They were in the heart of Arikara country and could hardly afford to wait any longer. Henry, a devote Christian, felt it necessary that Hugh Glass receive a proper burial. He asked for volunteers, and when no one stepped forward, he upped the ante. Henry included a hefty bonus to whoever would stay back with Glass, and bury him when he died. A young man near the back of the crowd, Jim Bridger, a boy of only 17 stepped forward. He was in desperate need of money and the promise of an extra bonus, equivalent to one month’s pay was irresistible. Another man, Thomas Fitzpatrick volunteered for the extra money. Henry’s volunteers would not likely wait long for Glass’s death and would follow the expedition’s trail north and then west and catch up in a few days. Almost at once, the rest of the trappers pulled up stakes and headed up the Missouri River and out of the dangerous Arikara Indian country.

The others were no sooner out of sight than Bridger and Fitzpatrick began digging Glass’s grave. Once dug, they rolled him into it, where he landed with a thump, and covered him with a large buffalo hide and waited. What the volunteers thought would be a quick death turned out to be nothing of the sort. The old honorary Pawnee Indian was a stubborn old warrior and refused to die. What Bridger and Fitzgerald though would take minutes, lagged into hours, and as night began to fall, the two white men became increasingly nervous of the looming danger of the Arikara. Throughout the night, Glass fell in and out of consciousness. His gurgled gasps for air likely drove the two volunteers nearly mad. Somewhere in the darkness of night, the two fell asleep. As they awoke in the morning, they fully intended to find Glass dead. But he was not. Fitzgerald argued to leave Glass where he lay, and make a run for it. It was only a matter of time before an Arikara hunting party would pass their way. Bridger strongly opposed leaving the near dead Glass, but the elder Fitzgerald’s perseverance finally triumphed and he and Bridger grabbed Glass’s prized Hawken rifle, his hunting knife, and other provisions, threw a few shovelfuls of sandy earth on top of him and hurried up stream to catch up to the expedition. Early the next morning the duo caught up with Henry and the others and reported that Hugh Glass has succumbed to his injuries and was now dead and buried.

That should have been the end of that.

However, in the hours after Bridger and Fitzgerald’s hasty retreat, Glass on some detached and dim level of consciousness, mustered enough strength, through either pure will power or pure resentment, to sit up in his own shallow grave. The world around him was burly, but he was fully aware that he had been betrayed. Perhaps the rage now brewing ever stronger helped to pull him from the grave. Once on flat ground, he set his own broken leg. Glass knew he was literally hundreds of miles from safety and was in the middle of hostile Arikara country. An expert on wilderness living and survival he knew safety lie only in Fort Kiowa, some 250 miles to the west. Unable to stand, Glass began to crawl. His wounds were infected so badly that the skin began to die. Somewhere along the route, fearing gangrene, he tipped a rotting log and under it found a slew of maggots, at which point he laid his injured back into the squirming pile until they hate ate away the dying and infected flesh.

Meanwhile, the original expedition had traveled up along the Missouri River and then later the Grand River. Glass knew that this would be far too dangerous an endeavor so he chose to crawl south, to the Cheyenne River.

And crawl he did.

For six weeks.

He had set his leg, but it was still too badly broken to support his weight. He ate berries and robbed ground-nesting birds of their eggs. He crawled to a recent buffalo kill and stayed three days at its side eating the meat. When he made it to the banks of the Cheyenne River, sometime in mid-September, his wounds had almost entirely healed. On the river’s bank he fashioned a crude raft and took the river into Fort Kiowa, another two week journey. He survived on frogs, raw minnows and river slime scooped by hand. Finally, upon arriving in Fort Kiowa in the cold days of early October, Glass rested only a few short days before hitching up with another trapping outfit headed in the direction of The Bighorn River. He planned, once at the Big Horn, of leaving the outfit to hunt down his old party and seek revenge on Bridger and Fitzgerald. The trapping outfit he was traveling with to The Bighorn River was being led by an experienced woodsman named Toussaint Charbonneau. Somewhere, miles into the trip, the party suffered hostile native attacks that left all but Charbonneau and Glass dead. Glass had once again narrowly escaped death. Afterwards, Glass parted ways with Charbonneau, who chose to continue traveling west with a tribe of Mandan Indians.

It would be a snowy December night before Glass finally arrived at Fort Henry at the mouth of the Yellowstone River. The past four months had taken him over 600 miles across the most dangerous land in the Western reaches of the United States. By this time, he was again nearly starving and pushed on by what can only be speculated as pure hate and revenge. As he opened the door to the tavern where the company of his former expedition now sat, merrily gulping holiday ale, celebration must have surely turned to disbelief. Shock filled the room and a nervous Bridger stepped back and into a far corner of the open room. Glass held no reservations as to why he had come and boldly announced he was there to kill Bridger and Fitzgerald. Pacing the room until he found Bridger, the old trapper lowered his rifle in line with the 17 year old boy. Bridger, who had every intention of staying with Glass, was so shocked and his guilt so apparent, that Glass, the hardened man who had crawled two months through a living hell, the man who hid from Indians, watched members of his own party murdered and ate rotting meat from the corpses of animals, forgave him almost immediately. But, the older Fitzgerald was another story. Glass asked the whereabouts of Fitzgerald and Andrew Henry had to inform Glass, that Fitzgerald had quit the expedition to join the Army. Upon hearing this news, Glass halfheartedly joined the trappers in the New Year’s celebration, but, as he drank the warm beer, his mind was on Fitzgerald.

In the days that followed, Glass acquired as much information as he could regarding the current location of Fitzgerald and tracked him to an army installation in Fort Atkinson, 30 miles north of modern day Omaha, Nebraska. It was the early summer months of 1824. Glass was stopped shortly before entering camp by the army Captain Bennett Riley. For months, word had spread of Glass’s search for the solider Fitzgerald and Captain Riley was not in any mood to have a man under his command murdered. Informing Glass that killing a soldier in the United States Army would result in his hanging, Glass reserved himself. He asked only that Fitzgerald return to him his prized Hawken rifle, to which Fitzgerald complied.

And then Glass disappeared.

An account of Glass being wounded by arrow one year later would surface in Naval medical records and it is known that he survived the attack, but nothing was to be written, or heard of Hugh Glass afterwards.

In a tale that could only have originated in the vast expanses of the American West, Glass embodied the grit, determination and sheer will power of the early American spirit. His intentions slightly skewed, he never the less survived a mountain man’s peril, and then appropriately and fittingly vanished into legend.

Bruce Bradley, Hugh Glass, 1999

John Myers, The Saga of Hugh Glass: Pirate, Pawnee and Mountain Man, 1976

Robert Mc Clung, Hugh Glass: Mountain Man, Left for Dead, 1993

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)