Wednesday, September 19, 2012

A River Story: The Stirring and Piteous Case of an Old Fashion Homestead Razing

It’s a late August morning when I arrive and pull my truck to the side of the road. In the years since I’ve last been here last, the road’s been paved wider and there’s barely enough room for me to park the truck on the gravel shoulder. There’s far more traffic too, even at this early hour and even for this quiet road. One car races by, narrowly missing me. I reserve little doubt that the motorist clearly saw me. He attempted instead to make a point of his nausea with me being parked so close to, what he contemptuously believes to be his own personal thoroughfare. Replying with an illustration of my own subtle distain, I hoist a single fingered salute in his direction.

The air is cool, you might even say brisk, but this August has been hotter than any I can remember. In a few hours I’m sure it won’t disappoint. A band of murky orange clouds smolder on the eastern horizon where the sun promises to rise. To watch the sky lighten in the still air of the morning is a privilege that I indulge myself in. I concluded long ago that sunsets are for hapless poets, teenage lovers, and people who have apparitions of enjoying nature but only within the confines of human convenience. But sunrises on the other hand must be earned. Watching the sun rise out over the world takes an act of purposeful discipline.

I begin attending to the job of removing the canoe from the roof of my truck. The night before, in what can only be described as a spectacle of sweat, swirling mosquitoes and uncontrolled convulsions of four-letter words, I affixed the ancient behemoth to the Ford and looking at it now, adhered so neatly, I hardly dare remove it. The 1952 Grumman is a relic of whose origins remain a mystery. It was a fixture alongside our family’s barn in south-eastern Wisconsin for as long as I can remember. It’s dented, scratched and has three holes in the bottom that suspiciously look as if they were put there by a 45 caliber pistol. My dad, seizing an opportunity at masculine ingenuity, had run half-inch bolts through the holes and from time to time a healthy dose of rubber silicone glue was needed to ensure its seaworthiness.

Rendering a slapdash verdict, I raise my knife to the ropes that held the canoe steadfast and cut them. Pulling the beast from the roof it’s suddenly like a whale out of the water as it tumbles to the ground. I jumped back anticipating it smashing into me like a spooked horse. After a few moments of convulsing wildly it comes to a rest. Much older than the 10 year old boy of my past, who needed to con unsuspecting friends into helping me to drag it, I now easily lift it from the bow and pull it along the gravel and to the banks of the river. The aluminum across the gravel is like the screeching of a Martini-pickled mother-in-law. But once at the bank, and after sliding the oversized tin can into the water, it becomes a different beast all together. The canoe is light and nimble as the unseen fingers of current tug gently at the hull and with a slight hop, we’re off.

The river is an old friend and looking back, I must admit rather grudgingly, one of my better ones. Growing up a farm kid, the river running through our property was as much a part of my childhood as my mom and dad, the sandbox, the old green barn to the north of our house or the tire swing tied to that massive red oak. It feels like home, but I prepare myself. This is to be a trip paid in homage, it is a good bye of sorts, a journey along a path that will take me thorugh flashbacks of my childhood, innocent and carefree but end in a sudden, undeniable modern realization of what lies ahead for this river.

The sun has just begun to peek above the horizon as I round my first bend. Streams, creeks, rivers, whatever you call them, they are engrained into our conscience, they are history before us, a story of time written across the landscape. They carried Native Americans along routes to sacred hunting grounds and the earliest explorers paddled them into wild and untamed new worlds. Their power is unimaginable. They can flood their surroundings in seconds, destroying all that lie in their path, and yet in the same breath gently bring water from far off sources to the forests and fields downstream, spreading life. This river knew me as a pink shouldered boy too young yet to notice girls, when I knew nothing of IRAs, and before I knew houses could be upside down. The world since then has grown and yet time seems to have frozen this place into a museum. Progress has not yet made it to the banks of this river. Gliding silently along, there is only the cadence of my paddle and the drops of water that fall from it. Peering into the heavily canopied forest, there is a light fog still clinging stubbornly to the forest floor. The sunlight has just now broken through the leaves, spilling scattered puddles of light across a mossy green carpet. Huge cottonwoods, weeping willows and silver birch line the shores; years of flood and frost have mangled their low hanging branches into the shapes of dilapidated play ground equipment, long deserted. These magnificent trees seem almost watchful over me, their roots imprisoning them to an eternal guardianship over this place. Like giant soldiers from a JRR Tolkien novel, they peer down as I float by.

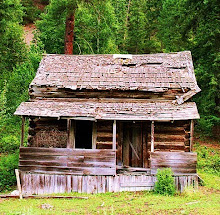

My nostrils are suddenly filled with the rich and heavy scent of rain in the distance. The muggy August morning is about to fracture. A gentle rolling breeze has kept the bugs at bay and the sun is now a phantom behind the clouds. A crack of thunder in the distance dazes me into a foggy memory of youth. It was near this spot that I once came as close to death as a young 15 year old might. In the summer before my freshman year, I had stuffed a pack with modest provisions and canoed 6 or 7 miles downstream from my house. The river was low that summer. We had been plagued with drought for months and where water had traditionally been shallow, numerous sandbars had now formed. It was one of these sandbars I thought would be a perfect place to build camp. Feeling rather smug, I built a fire and cooked rations of Spam, stolen from my mother’s cupboard and watched the sun sink in the sky without a care in the world. Sometime around 2 am that night, I awoke to the clap of thunder and the gentle pitter-patter of rain on my tent. With-in seconds the pitter-patter had turned to a hammering down pour. Reaching for my lantern, I looking down and noticed water several inches deep. During a normal summer the sandbar would be under seven or eight feet of water. A massive lump formed in my throat. Rushing from my tent, I searched for the canoe, but it was gone. I had failed to tie it to anything the night before, feeling no need to do so. In a panic, I tried gathering up my camping gear, a foot of water was now swirling at my ankles. As I un-staked my tent the true power of a mere twelve inches of water made an ever-lasting impression on my psyche as the water pulled the tent effortlessly from my clinched hands. Somehow I managed to grab my life jacket seconds before the tent vanished into the blackness of the raging storm. Just as the current knocked me from my feet, I was able to wrestle it on and a watery abyss suddenly enveloped me. To this day, I have never experienced anything like it. Suddenly, over the roar of the rain and thunder, to my ears came what I can only describe as a low, thundering growl, rumbling through the blackness. Gasping for air and being tossed like a rag doll, my head pulled under, then back above, I was suddenly hit square in the face by what felt like a brick wall. In an instant, I found myself completely submerged and unable to tell neither which way I was facing, nor which way was up or down. I surfaced what felt like several minutes later, only to find myself in the center of an electrical storm beggaring description. Lightning flashed everywhere and my surroundings looked as though they were being illuminated by a strobe light. A seemily foreign world enveloped me, catching glimpses of my surroundings only in erratic flashes. It completely disoriented me. The water slammed me from one side of the shore to the other. Low hanging branches reached for me like the cold boney fingers of the grim reaper. And then everything went black. I’m not sure how long I was out, but I woke suddenly, on my back and staring up at a full moon and wispy gray clouds. A dull pain throbbed in the back of my head and I could still see faint flashes of lightning in the distance as the passing storm raged on to the east of me. Finding myself floating in a backwater eddy, I peered through the moonlit darkness at an unfamiliar looking river bloated with flood. Paddling myself into the main current, I let it take me. Barefoot and having little more on than some cut off jeans, I was 10 miles from home and floating now in the wrong direction all together. I was without my canoe and without any supplies. Drifting along for what seemed to be an hour, I caught a glimpse of something silver and foreign in the inky blackness ahead. Tangled in the branches of an old willow tree was the canoe. Swimming to it, I somehow monkeyed myself into the hull. I waited the night out cold, alone and with a new found respect for the river, water, and the wild. The next day to my relief I discovered I was only a short mile from where the river went under the bridge at old Highway 67. Once there I flagged down a driver who took a chance on a skinny half naked kid alongside the road. Now all these years later I’m peering down into the same water, clear as gin, sad I suppose that this is the last I’ll ever see it so lucid, so pristine, and so untouched. Not more than a half mile to the north lay the unmistakable manifestation of Progress. A vast cesspool of new construction, land, that only weeks ago looked very much as it had for over a hundred years, now stands absolutely devoured. The area, once a family farm, tilled by countless generations, is a wasteland where the preemptive stages of what they call growth now stretch out over a thousand acres. It is a landscape void of any character or reason. Farming has always been hard work, and it never paid well. Even as the government seemed to come to its senses during the 1980s, passing legislation that helped families keep their farms, Big-Farm-a, as I call it, squeezed the chance at any real profit from the husband and wife dairy farmers. Tyrants have long realized that land is a scared birth-rite, and to take it, by means of taxation, bribery, eminent domain or rapacious persuasion is a psychological means of warfare, leading to eventual slavery by the state. Regardless of the terms of this sale, the signatures on the contract weren’t yet dry when the army of bulldozers, excavators, back-hoes, and dump trucks laid siege to the land. The mayor with various cronies of political hierarchy were there to witness the groundbreaking, as were some lawyer types, developers, bankers and investors. Standing in the middle of the chaos that was to be, stood the empty farmhouse, the symbolic enemy, what it represented was in sharp contrast to everything the developers planned on building in its place. The razing of the old homestead was to be celebrated by the pale-faced hacks who watered at the mouth by the mere thought of its demise. A lone bulldozer set forth at accomplishing the task at hand. It came from the north and struck the house with full force. The lawyers and the banker-backed developers stood in perverted anticipation. But the structure did not immediately fall. The operator looked on in amazement. He readied the machine for another blow. The mayor peered on with distain, how this dilapidated little shack dare stand in the way of progress he thought. The bulldozer struck again with full force. The old farm house shuttered but stood on rebelliously. But in the end, it was only made of wood, and the bulldozer of iron, fueled by diesel, greed and the full momentum of progress behind it. When the house was gone the mayor and the stiffs in the suits stood triumphantly for pictures on the newly conquered ground. Construction trailers were brought in at once and placed at the site of the old homestead and a flag was raised in victory over the farm. And then began the rape and pillage. Earthmovers rolled in, by the dozens. There was a sick feeling of inhumanness that hung in the air; a sense of an almost robotic, unfeeling movement. Nothing with a soul could do what was being done there. The machines sheared the ground and peeled earth back, crops still in place, like skin scalped from the skull. Total destruction and extermination of any human spirit left in this place was the goal. With-in a few days the once teaming landscape was reduced to a barren wasteland. Dust blew across the real estate as if it were a desert. There was about as much life left there as was on the moon. So much as I once believed that a God would never allow such a faith befall this place, I also now come to the realization that it is lost. A family of Canada geese floats past my canoe, a proud hen with five goslings in tow. A nervous gander swims at a distance and gives me the evil eye. Martin Luther King, Jr. said once, “if I knew the end was to come tomorrow, I would still plant my apple tree.” The tiny family swims on and out of sight, unaware of the destruction that awaits them. Or perhaps they are all too aware and instead wish to heed the mind set of Dr. King and swim on. My take out spot is just ahead. I have stashed a bike somewhere there in the cattails as a means by which to get back to my truck some twelve miles or so upstream. I’ve been to this place many times before. Here the river narrows and the water flows faster than anywhere else. A chessboard of rocks sticks out from the surface and the water rushing around them is like a chorus. I used to love spending time here at the end of each trip simply sitting and listening to the water. So assuring was that sound, assuring that there existed something so much more complex than our own derisory existence. Assuring that something as random as rocks placed in the water by time could reverberate a sound so diverse in its simplicity. These waters have called to me my whole life. From the pre-pubescent boy who gathered river rocks, to the adolescent who tried to forget the hardships of high school here or the young man who sat in this very spot trying to gather the courage to tackle the life ahead of him, I have relied on this river for so much strength, and now there is nothing I can do to protect it. I pull the canoe from the water one last time, leaving it in the bulrushes a dozen or so feet from shore as a fitting final resting spot, here at the river where it belongs. As I walk to the road, I can hear the water behind me. It’s a sad voice that seems not to understand my parting. I don’t answer, I simply turn my back and walk away.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)